St James

West Tilbury, Essex

© Nigel Anderson - St James Trust

Queen Elizabeth

Background

On his marriage to Mary Tudor (only child of Henry VIII and

Catherine of Aragon) Phillip II of Spain became King of England and

Ireland, until Mary’s death in 1558. The throne was then inherited by

her half-sister, Elizabeth. As a devout Roman Catholic, Phillip

deemed Mary's half-sister Elizabeth a heretic and illegitimate ruler

of England. He had previously supported plots to have her

overthrown in favour of her Catholic cousin and heir presumptive,

Mary, Queen of Scots, but was thwarted when Elizabeth had Mary

imprisoned, and finally executed in 1587.

In addition Elizabeth had supported the Dutch Revolt against Spain

and in retaliation Philip planned an expedition to invade England,

overthrow the Protestant regime of Elizabeth, and cut off the English

attacks on Spanish trade and settlements in the New World.

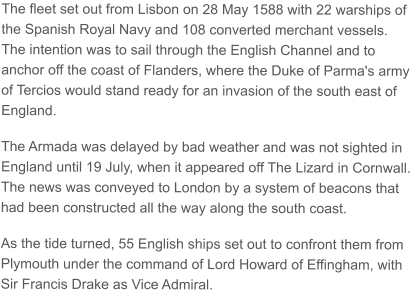

The Spanish Armada

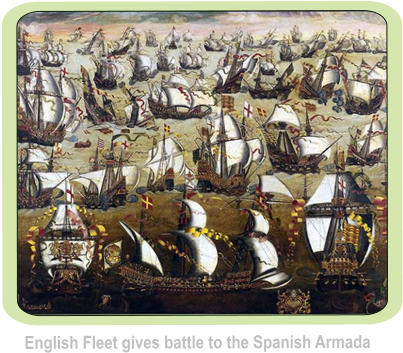

The Armada anchored off Calais on 7 August, in a tightly-packed

defensive crescent formation, but were forced to cut their cables in

confusion when the English set alight eight fireships and cast them

downwind among the closely anchored Spanish vessels. No Spanish

ships were burnt, but with the crescent formation now broken, the English

closed in for battle.

After eight hours, the English ships began to run out of ammunition, and

around 4pm, the English fired their last shots and were forced to withdraw.

Five Spanish ships were lost while many other Spanish ships were

severely damaged.

The Spanish plan to join with Parma's army had therefore been defeated

and the English had gained some breathing space, although the Armada's

presence in northern waters still posed a great threat to England.

In September the Armada’s return trip to Spain (around Scotland and Ireland) proved decisive as the Spanish ships were struck by

a series of powerful westerly gales. In the end only 67 ships and less than 10,000 men survived the journey and it was reported

that, when Philip II learned of the result of the expedition, he declared, "I sent the Armada against men, not God's winds and

waves".

English losses stood at only 100 dead and 400 wounded, with none of their ships having been sunk. The resounding victory put to

rest any further invasion plans.

Over the next few days the English ships used their superior speed and manoeuvrability to harry the Spanish fleet so that the Armada

was compelled to make for Calais rather than their intended base in the Solent.

The Battle of Gravelines

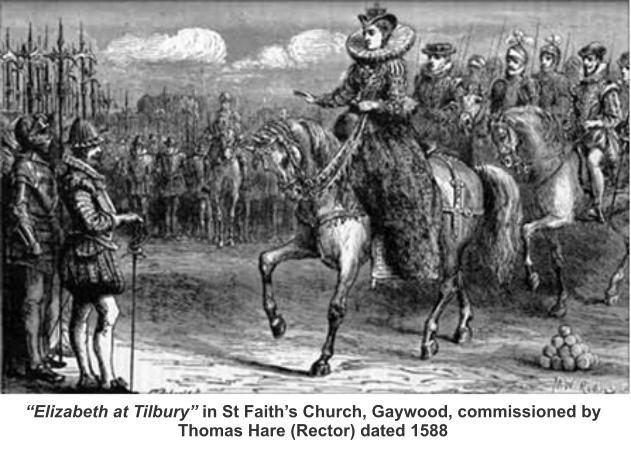

The ‘Apothecaries’ painting of 1588 by Nicholas Hilliard.

A stylised depiction of key elements of the Armada story: the alarm beacons, Queen Elizabeth at

Tilbury, and the sea battle at Gravelines

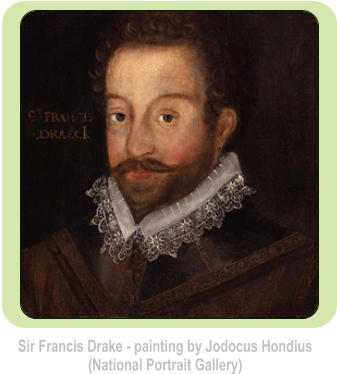

The West Tilbury Speech

After the Battle of Gravelines and with the threat of invasion from the

Netherlands not yet discounted, Robert Dudley (Earl of Leicester),

who had been appointed Lieutenant and Captain General of the

Queen’s Armies and Companies, gathered a force of over 17,500

soldiers at West Tilbury, Essex.

This was to defend the Thames Estuary against any incursion up-river

towards London and a blockade of boats across the Thames was also

put in place to deter any invasion.

The royal barge, carrying Queen Elizabeth I, arrived at Tilbury on the

8 August 1588. She spent two days here and, after spending the night

at Horndon on the Hill, she returned to West Tilbury the next day to

give her famous speech, directly aimed at encouraging her forces in

the anticipated fight against teh Spanish invaders.

“My loving people, we have been persuaded by some that are careful of our safety, to take heed how we

commit ourselves to armed multitudes for fear of treachery; but, I do assure you, I do not desire to live to

distrust my faithful and loving people.

Let tyrants fear, I have always so behaved myself, that under God I have placed my chiefest strength and

safeguard in the loyal hearts and goodwill of my subjects; and, therefore, I am come amongst you as you

see at this time, not for my recreation and disport, but being resolved, in the midst and heat of battle, to

live or die amongst you all – to lay down for my God, and for my kingdoms, and for my people, my honour

and my blood even in the dust.

I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king – and of a

King of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to

invade the borders of my realm; to which, rather than any dishonour should grow by me, I myself will take

up arms – I myself will be your general, judge, and rewarder of every one of your virtues in the field.

I know already, for your forwardness, you have deserved rewards and crowns, and, we do assure you, on

the word of a prince, they shall be duly paid you. In the mean time, my lieutenant general shall be in my

stead, than whom never prince commanded a more noble or worthy subject; not doubting but by your

obedience to my general, by your concord in the camp, and your valour in the field, we shall shortly have

a famous victory over those enemies of my God, of my kingdom, and of my people”

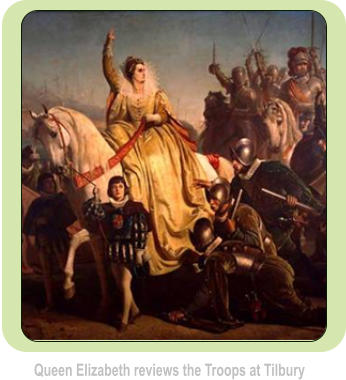

Tilbury Fort

Tilbury was picked as the point of assembly as it was also the site of the main

Thames defensive fort, originally built in 1539 by Henry VIII on the site of a

dissolved hermitage, hence its original name “The Hermitage Bulwark” or

“Thermitage Bulwark”.

It had originally been built as a D-shaped blockhouse and was designed to

cross-fire with the Gravesend Blockhouse (built in the same year), but as the

treat of invasion by France had diminished, the fort had been decommissioned.

With the fresh threat of a Spanish invasion, emergency improvements to the

fortifications were made by Robert Dudley (Earl of Leicester) and over the

course of the next year the Italian engineer, Federigo Giambelli, reinforced the

blockhouse further with a precursor to the famous star-shaped line of

earthworks, that were later built on its landward side.

On the day of the speech, the Queen left her bodyguard before the fort at Tilbury

and went among her subjects with an escort of six men.

Lord Ormonde walked ahead with the Sword of State; he was followed by a page

leading the Queen's charger and another bearing her silver helmet on a cushion.

Then came the Queen in white with a silver cuirass and mounted on a grey

gelding. She was flanked on horseback by the Earl of Leicester on the right, and

on the left by the Earl of Essex, with her “Master of Horse” Sir John Norreys

bringing up the rear.

This speech demonstrates Elizabeth's courage and fortitude in the time of war at

one of the most trying times for her troops. Ultimately, this is one of the events she

is best-remembered for, where she gracefully and powerfully explains:

"I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart

and stomach of a king, and a king of England too."

The Church of St James

The actual site where the troops gathered is not clear but records indicate that it was

probably just outside the village centre near the windmill, although other authorities

indicate that it may have been the high ground surrounding St James’ church

Irrespective of the actual location of the site, St James was to play an important role

in the defensive strategy. With its high stone tower St James’ was certainly the most

likely visual communications station to have served the Armada camp.

It would have been key in conveying signals via all waterfront blockhouses,

Leicester’s pavilion atop Gun Hill, the fort at Gravesend and the ports of the Downs,

(exploiting the Kentish hilltops) while Eastward, it looked far beyond Sheppey, where

the uppermost turrets of Queenborough held another beacon facility.

Ranging the Thames during the invasion scare were also two specially appointed

watch vessels, the ‘Victory’ and ‘Lion’, while the fishermen of Leigh – a small seaport

also visible from the West Tilbury – were primed to give warning of the presence of

any hostile galley. Leigh’s pale fifteenth century tower still carries its masonry

beacon turret, as does that of the nearer church of St. Michael’s, Fobbing.

On 1 November 1588 the churchwardens of West Tilbury were accused by the

archdeacon of neglecting their church wall and furniture. They replied:

“…..that by meanes of the Campe that did lie there, there churche stooles and

wall is muche broken downe”.

The archdeacons response was pragmatic and they were allowed eleven months to

put this right - at their own expense! (Ref 21).

Certainly it would appear that the church was vandalised by soldiers from the Earl

of Leicester’s Armada camp and a quote by William Browning (one of the Bailiffs of

Maldon) that:

“…..there weere non at Tylburye Campe but Rogues and Rascalls…..”

was probably not too far from the truth.

The Aftermath

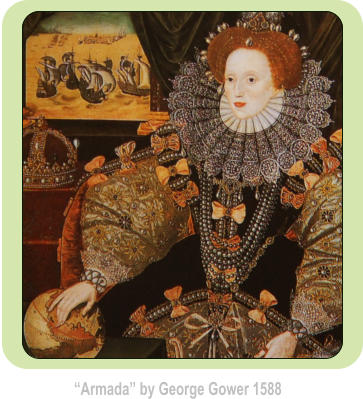

Armada (George Gower circa 1588)

The famous Armada portrait of Elizabeth I, painted around 1588, celebrates the defeat of the Spanish Armada. Details

show the main sea battle and the Spanish ships floundering in the storms. The queen’s hand rests on a globe, suggesting

her new international power. The painting, executed soon after the event, is attributed to George Gower (1540-1596),

Sergeant-Painter to the Queen.

The Bridgeman Art Library 5524